“The characteristic of an English country dance is that of gay simplicity. The steps should be few and easy, and the corresponding motion of the arms and body unaffected, modest, and graceful.” – The Mirror of Graces, 1811

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wqC2DlB8P1Q&w=420&h=315]

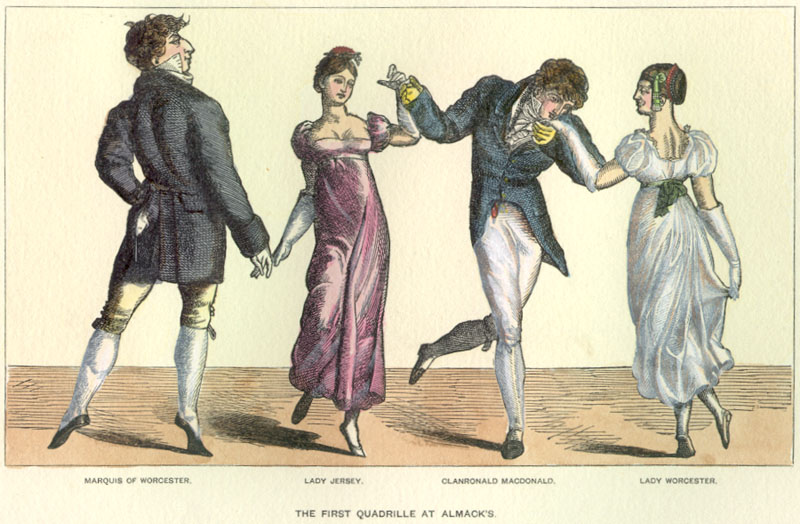

Above is an example of the Quadrille

In a society governed by strict rules regulating the interaction of the sexes, the dance floor provided one of the only places marriage partners could meet and courtships subsequently blossom. The ballroom guaranteed respectability and proper conduct for all parties since they were carefully regulated and chaperoned. Even so, under cover of the music and in the guise of the dance, young people could talk and even touch in ways not permitted elsewhere.

As far as the opportunity to meet people went, private balls had the very great advantage over public ones in that the hosts controlled who attended. One could be assured of the quality of guests at a grand house, so chaperons could rest a little easier that their charge was not interacting with someone below her station.

Hosting a ball was no small matter. Musicians had to be hired and supper for all the guests provided. Cards or invitations were sent out no less than two to three weeks prior to the event and a reply was imperative within a day or two. After the ball, thank you notes were expected of all the guests in appreciation for the hospitality.

Dressing for a ball

Balls were, of course, formal occasions which allowed one to show off their finery. But even here, there were degrees of formality. The dress ball which usually began with minuets was the most formal, a cotillion ball somewhat less so. ‘Undress’ or ‘fancy’ balls invited the guests to appear in all manner of historical or fanciful costumes. Whatever the form of dress, gloves were essential lest the dancers touch one another directly.

Opening the ball

Early in the Regency era, balls were opened with a minuet. By the early 1800’s the practice fell from favor as it took far too long for all the couples to have a turn to display in the slow, elegant dance.

Later in the period, the ball would be opened by the hostess, the lady of highest rank or the person in whose honor the ball was given (like a debutant or new bride) who took the top position of the first dance. The top lady would ‘call the dance’, determining the figures, steps and music to be danced. Polite young ladies were cautioned that if they should lead a dance they should not make the figures too difficult for the other dancers, especially if there were younger dancers present.

Dance Partners

Every dance required a partner. At a private ball, unlike a public assembly, everyone was considered introduced, so any young man could ask any young woman to dance. A young lady signaled she was interested in dancing by pinning up the train of her gown. If asked to dance, she could not refuse unless she did not intend to dance for the rest of the night.

Gentlemen, unless they retired to the card room, were expected to engage a variety of partners throughout the evening. Failing to do so was an affront to all the guests. A gentleman might request a dance in advance, but saving more than two dances for a particular partner was detrimental to a young lady’s reputation.

Oftentimes women outnumbered men at these affairs. As a result, it was not uncommon for women to dance with other women rather than sit out the entire evening.

Food

Halfway through the evening, dancers would pause to refresh themselves with a meal. Soup, especially white soup (made from veal or chicken stock, egg yolks, ground almonds and cream) served with negus (sugar mixed with water and wine, served hot) were staples. One’s dance partner for the ‘supper dance’ usually would be one’s dining partner for the meal as well.

Dances

Supper was quite necessary as most of the ball dances were lively and bouncy. Country dances, the scotch reel, cotillion, quadrille made up most of the dancing.

In the country dance, a line of at least five couples progressed up and down the line in various figures as dancers would swing from partner to partner. Country dances basically had only one step that was used to create various chain patterns and shapes along the dance floor. As they reached the top, each couple in turn would dance down until the entire set had returned to its original positions. These dances were very flexible in the number they could accommodate.

In large sets, this could take an hour to complete.

Some insisted that reels were better suited to private balls than public assemblies because of their merry character. In this dance four, or sometimes six, dancers would perform interlacing figures with one another then pause for a sequence of fancy footwork similar to a Highland Fling.

The cotillion was a French import, with elaborate footwork. It was performed in a square or long ways, like the country dance. It consisted of a “chorus” figure unique to each dance which alternated with a standard series of up to ten “changes” (simple figures such as a right hand star) common to cotillions in general. Some considered cotillions out of fashion by 1800.

The quadrille was a dance for four couples arranged in a square. It consisted of five distinct parts or figures assembled from individual cotillions. Without the changes it was a much shorter dance. The music for the dance was often adapted from popular songs and stage works.

One dance not likely to be found in a Regency era ball was the waltz. When it was first introduced, the waltz was regarded as shocking because of the physical contact involved. Even Lord Byron was scandalized by the prospect of people “embracing” on the dance floor. It was unlikely to have been seen often in public assemblies until the latter part of the Regency era, and even then, not often.

For a wonderful animated tour of the figures danced check out this site: http://rivkinetic.org/flash/ecdflash.html.

References

A Lady of Distinction. Regency Etiquette, the Mirror of Graces (1811). R.L. Shep Publications (1997)

Britain Express: Regency Dances http://www.britainexpress.com/History/regency-dances.htm

Day, Malcom – Voices from the World of Jane Austen. David & Charles (2006)

Lane, Maggie – Jane Austen’s World. Carlton Books (2005)

Laudermilk, Sharon & Hamlin, Teresa L. The Regency Companion . Garland Publishing (1989)

Ross, Josephine – Jane Austen’s Guide to Good Manners. Bloomsbury USA (2006)

Selwyn, David – Jane Austen & Leisure. The Hambledon Press (1999)

Sullivan, Margaret C. – The Jane Austen Handbook. Quirk Books (2007)

Period References

The Complete System of English Country Dancing – 1815 (click to download pdf)

http://i963.photobucket.com/albums/ae114/dr_grace423/me.jpg

Maria Grace is the author of Darcy’s Decision and The Future Mrs. Darcy. Click here to find her books on Amazon. For more on her writing and other Random Bits of Fascination, visit her website. You can also like her on Facebook, follow on Twitter or email her.

Lovely post. I tweeted.

Thank you!

I noted that the Regency ball gowns were not to the floor or even to the base of the ankle, but higher. Probably better for dancing, too.

That’s very interesting. Thanks for stopping by Regan!

Much more fun way to exercise than going to the gym! I am tidying up my regrettably modern house today, but in my head I shall be dancing a cotillion with the best of them!

A great idea to make tidying more bearable!

PJK x

Why do a lot of Regency writers have waltz’s in their stories if it was so uncommenn then ?

Although it was uncommon, it was danced in the Regency era (in fact I have one in my book 🙂 ) as the period drew on, the waltz became more acceptable and even fashionable. Even the exclusive Almack’s with it’s sniffy patrons allowed it!

Does that help answer your question?

PJK x

Nice post!

Readers might be interested in a project to animate Regency era dances here: http://www.regencydances.org/ .